How God Makes Covenants: Understanding the Structure Behind the Bible’s Promises

When the Bible speaks about covenants, it is not inventing a new religious concept out of thin air. God chose to communicate His relationship with humanity using a form that people in the ancient world already understood. That form is what scholars call a suzerain–vassal covenant.

In the ancient Near East, a suzerain was a great king who ruled over lesser kings or peoples, called vassals. These covenants were not agreements between equals. They were initiated by the greater king, rooted in his authority, and designed to establish loyalty, protection, and order. Archaeology has uncovered many such treaties, including Assyrian and Hittite covenant texts carved on stone stelae or written on clay tablets, which closely mirror the structure found in Scripture.

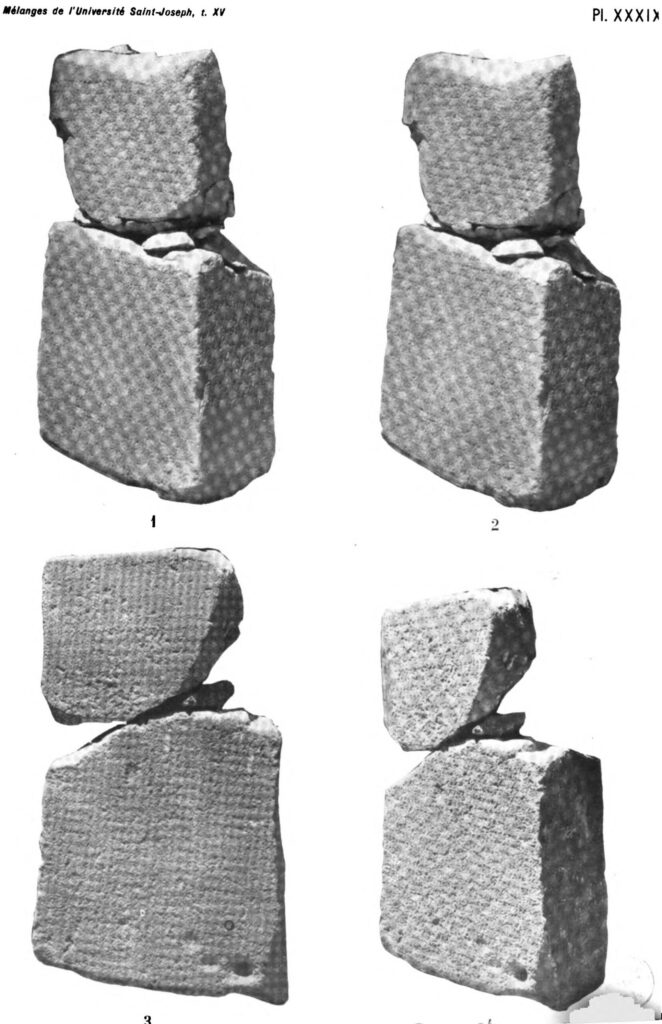

One well-known example is the Sefire Stelae, discovered in Syria, which record a covenant between an Assyrian ruler and a vassal king. These treaties typically included a preamble identifying the suzerain, a historical section describing past benevolence, covenant obligations, blessings for loyalty, curses for rebellion, witnesses, and a physical sign or record of the covenant. This same pattern appears repeatedly in the Bible, especially in God’s covenants with Israel.

What makes the biblical covenants unique is not their structure, but their character. Unlike earthly kings, God binds Himself to His people with mercy, patience, and enduring faithfulness.

Below you will find a list of the major covenants found in the scriptures and how they fit into this this structure.

The Covenant with Noah

The covenant with Noah is God’s covenant with all creation. After the flood, God promises never again to destroy the earth by water (Genesis 9:8–11). The provision is preservation of life and stability of the world. The obligation placed on humanity is minimal and universal, involving respect for life (Genesis 9:4–6). The sign of this covenant is the rainbow, set in the sky as a visible reminder of God’s promise (Genesis 9:12–17). This covenant emphasizes God’s commitment to sustaining creation itself.

The Covenant with Abraham

The Abrahamic covenant forms the foundation for everything that follows. God promises Abraham descendants, land, blessing, and a mission to bring blessing to the nations (Genesis 12:1–3; 15:5–7; 17:7–8). The covenant’s fulfillment rests on God’s promise rather than Abraham’s performance, though Abraham is called to walk faithfully before God (Genesis 17:1). The sign of this covenant is circumcision, marking covenant identity across generations (Genesis 17:9–14). This covenant is repeatedly described as everlasting.

The Covenant at Sinai

At Sinai, God establishes a covenant with the descendants of Abraham whom He has already redeemed from Egypt. The provisions define Israel’s calling as a holy nation and kingdom of priests (Exodus 19:4–6). The obligations are detailed in the Torah, shaping how Israel is to live faithfully within the covenant. Blessings and consequences follow the familiar suzerain pattern (Leviticus 26; Deuteronomy 28). The sign of this covenant is the Sabbath, a perpetual reminder of God as Creator and Redeemer (Exodus 31:13–17). Importantly, this covenant does not replace the Abrahamic covenant but operates within it.

The Covenant with David

God’s covenant with David focuses on kingship and continuity. God promises that David’s lineage will endure and that his throne will be established (2 Samuel 7:12–16). The obligation is faithful kingship aligned with God’s ways, though individual kings may face discipline (Psalm 89:30–34). The covenant sign is not a ritual object but the Davidic dynasty itself, upheld by God’s promise (2 Samuel 7:16). This covenant anchors Israel’s messianic hope.

The Promised New Covenant

Through the prophets, God promises a renewed covenant in which He will forgive sin, transform hearts, and internalize His instruction (Jeremiah 31:31–34; Ezekiel 36:26–27). This covenant does not annul previous covenants but brings their purposes to fulfillment. The provision is inner renewal and restored relationship. The obligation is transformed faithfulness empowered by God Himself. The sign is God’s instruction written on the heart—manifested by the Spirit (Jeremiah 31:31–34).

Why This Structure Matters

Understanding covenants through the lens of ancient suzerain–vassal treaties helps us see the Bible more clearly. God is the great King who initiates relationship, reminds His people of what He has done, defines how they are to live, and binds Himself to them with promises that endure even when they fail.

Most importantly, this structure reveals God’s character. Earthly kings enforced covenants through fear and coercion. God enforces His through faithfulness and mercy. Again and again, Scripture declares that He remembers His covenant and does not abandon His people, even in exile or failure (Leviticus 26:44–45; Psalm 105:8).

If God were like human rulers, His covenants would collapse under the weight of human unfaithfulness. But because He is not, His covenants stand. And because His covenants stand, we can trust that the God who bound Himself to Noah, Abraham, Israel, and David will also remain faithful to us. The structure of covenant is not a relic of the ancient world. It is the framework through which God reveals His steadfast love

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.